Fiscal Policy at Work | Economics |CBCS

The Determination of Equilibrium Output (Income)

Equilibrium occurs where Y = AE—that is, where aggregate output equals planned aggregate expenditure. Remember that planned aggregate expenditure in an economy with a government is AE C + I + G, so equilibrium is

Y = C + I + G

If output (Y) exceeds planned aggregate expenditure (C + I + G), there will be an unplanned increase in inventories—actual investment will exceed planned investment. Conversely, if C + I + G exceeds Y, there will be an unplanned decrease in inventories.

First, our consumption function, C = 100 + .75Y before we introduced the government sector, now becomes

Second, we assumed that the government is running a balanced budget, financing all of its spending with taxes. So, G=100 ,T=100 and planned investment (I) is 100.

Table calculates planned aggregate expenditure at several levels of disposable income.

For example, at Y = 500, disposable income is Y - T= 400. Therefore, C = 100 + .75(400) = 400. Assuming that I and G are fixed at 100, planned aggregate expenditure is 600 (C + I + G = 400 + 100 + 100). Because output (Y) is only 500, planned spending is greater than output by 100. As a result, there is an unplanned inventory decrease of 100, giving firms an incentive to raise output. Thus, output of 500 is below equilibrium.

In Figure, we derive the same equilibrium level of output graphically.

Finding Equilibrium Output/Income Graphically: Because G and I are both fixed at 100, the aggregate expenditure function is the new consumption function displaced upward by I + G = 200. Equilibrium occurs at Y = C + I + G = 900.

Now in addition to 100 in investment, we have government purchases of 100. Because I and G are constant at 100 each at all levels of income, we add I + G = 200 to consumption at every level of income. The result is the new AE curve. This curve is just a plot of the points in columns 1 and 8 of Table .

The 45° line helps us find the equilibrium level of real output, which is 900. If you examine any level of output above or below 900, you will find disequilibrium. Look, for example, at Y = 500 on the graph. At this level, planned aggregate expenditure is 600, but output is only 500. Inventories will fall below what was planned, and firms will have an incentive to increase output.

The Saving/Investment Approach to Equilibrium

The government takes out net taxes (T) from the flow of income—a leakage—and households save (S) some of their income—also a leakage from the flow of income. The planned spending injections are government purchases (G) and planned investment (I). If leakages (S + T) equal planned injections (I + G), there is equilibrium:

saving/investment approach to equilibrium: S + T = I + G

Let's derive this, we know that in equilibrium, aggregate output (income) (Y) = planned aggregate expenditure (AE).

By definition, AE = C + I + G, and Y = C + S + T. Therefore, at equilibrium

C + S + T = C + I + G

Subtracting C from both sides leaves:

S + T = I + G

Fiscal Policy at Work: Multiplier Effects

If the government were able to change the levels of either G or T, it would be able to change the equilibrium level of output (income). At this point, we are assuming that the government controls G and T.

In this section, we will review three multipliers:

- Government spending multiplier

- Balanced-budget multiplier

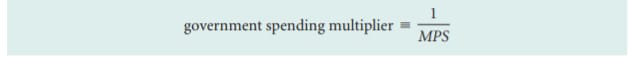

The Government Spending Multiplier

Suppose the economy is sitting at the

equilibrium output pictured above. Output and income are 900, and the government is

currently buying 100 worth of goods and services each year and is financing them with 100 in

taxes. The budget is balanced. In addition, firms are investing (producing capital goods) 100.

We now need to determine how the government can use taxing and spending policy—

fiscal policy—to increase the equilibrium level of national output. To increase spending without raising taxes (which provides the government with revenue to

spend), the government must borrow. When G is bigger than T, the government runs a deficit

and the difference between G and T must be borrowed. For the moment, we will ignore the possible effect of the deficit and focus only on the effect of a higher G with T constant. The increased government

spending will throw the economy out of equilibrium. Because G is a component of aggregate

spending, planned aggregate expenditure will increase by 200. Planned spending will be greater

than output, inventories will be lower than planned, and firms will have an incentive to increase

output.

The moment output rises, the economy is generating

more income.The newly employed

workers are also consumers, and some of their income gets spent. With higher consumption

spending, planned spending will be greater than output, inventories will be lower than planned,

and firms will raise output (and thus raise income) again. This time firms are responding to the

new consumption spending. Already, total income is over 1,100.It is the multiplier in action.

Although this time it is government spending (G) that is changed rather than planned investment (I), the effect is the same

as the multiplier effect. An increase in government spending has the

same impact on the equilibrium level of output and income as an increase in planned investment. The equation for the government spending multiplier is the same as the equation

for the multiplier for a change in planned investment.

Government spending multiplier - The ratio of the change in the

equilibrium level of output to a

change in government spending.

This is the same definition we

used in the previous chapter, but now the autonomous variable is government spending instead

of planned investment.

Now, we can check our answer to make sure it is an equilibrium.

Look first

at the old equilibrium of 900. When government purchases (G) were 100, aggregate output

(income) was equal to planned aggregate expenditure (AE = C + I + G) at Y = 900. Now G has

increased to 150. At Y = 900, (C + I + G) is greater than Y, there is an unplanned fall in inventories, and output will rise.

The multiplier told us that equilibrium income would rise by four times the 50 change in G.

Y should rise by 4*50 = 200, from 900 to 1,100,

before equilibrium is restored. Let us check. If Y = 1,100, consumption is C = 100 + .75Yd

= 100 + .75(1,000) = 850. Because I equals 100 and G now equals 100 (the original level of G) +

50 (the additional G brought about by the fiscal policy change) = 150, C + I + G = 850 + 100 +

150 = 1,100. Y = AE, and the economy is in equilibrium.

The graphic solution, an increase of 50

in G shifts the planned aggregate expenditure function up by 50. The new equilibrium income

occurs where the new AE line (AE2) crosses the 45° line, at Y = 1,100.

Don't forget to Subscribe for updates.

Do like, comment and share.

Comments

Post a Comment